robertsanchez

Usuario Regular

Mar 7, 2009, 7:40 PM

Mensaje #3 de 3

(12109 visitas)

Link

|

ALGO MAS

Broadacre City  Frank Lloyd Wright Frank Lloyd Wright  and his vision for the urban future and his vision for the urban future

Franz Sdoutz, June 1999, May 2007

Deutsche Fassung

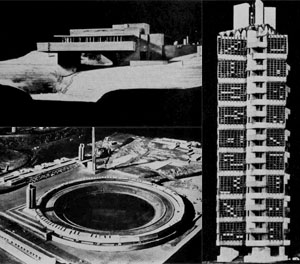

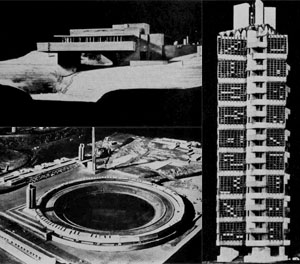

Abb. 01

Broadacre's vast suburban landscape, seemingly scattered across an entire continent, anticipates the prevailing urban context, that eventually will shape the condition of architecture. With hindsight BROADACRE CITY (1932-1958) appears premonitory of current states. An assessment that still adds to the accumulative aura surrounding its initiator FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT (1867-1959). Abb. 02

Broadacre City, Frank Lloyd Wright's urban utopia for the U.S. continues to intrigue, as illustrated by Columbia University students in 1997. Their computer animation renders Wright's vision according to drawings entitled "THE LIVING CITY", published first in 1958. Abb. 03

1932 - 26 years earlier, at the age of 65, Frank Lloyd Wright has reached the end of his first carrier. Two years without commissions affect his finances badly, though the true personal and economical calamities of his life already lie behind him.

At the time (1932) Philip Johnson says of Frank Lloyd Wright: "He is the greatest architect of the 19.th century." VI.) 1

An insult, triggered off by the generation gap, but also by Wright's architecture. The International Style (named after a noted exhibition in same year, featuring Wright at MOMA - New York X.) 7) spearheads the Avant-Garde. Modernism has changed since Unity Temple 1906, Robie House 1908 and Imperial Hotel 1915-21.

Wright is deemed an outsider. Abb. 04

Europe sets the stage for Wright's comeback. Le Corbusier formulates his ideas for the future, designing a contemporary city for 3 million inhabitants. In 1922 the principles are clear. This city is dense, rational, organised; to put it in a nutshell - urban. Abb. 05

Wright's answer is as radical as it is diametrically opposed. Broadacre isn't a city; it is a landscape. Decentralised in organisation it is self-sufficient in supply, republican in constitution, and populated by auto - mobile citizens.

Centred on the homestead, the single family house, Broadacre sprawls.

Wright lives this Arcadian lifestyle with his apprentices he gathers around him. The "Taliesin Fellowship" puts the green republic to the test. Their aim is to pursue happiness. Abb. 06

Wright perceives himself and his rebellion as "an army under siege". The atmosphere in Taliesin at the time is described like this:

"It was not a civilized situation - it was a heroic one." VI.) 2

From this milieu emerges the plan for a community laying out their cities according to family values, spirituality and knowledge.

Everyone owns land for cultivation, at least one acre (4046,8m2, 165 by 264 Feet). The model plan covers four square miles. Abb. 07

Property is the economic basis.

Market economy - yes, but in the shape of trade by barter between proprietors. (Rent is synonymous for all ills in the contemporary city.) XI.) 8

Economy is considered to work like an agricultural fair. Its site is the huge marketplace.

Broadacre is a community without experts. Everyone does everything. Everyone's a farmer - industrial worker - artist: reminiscence of the "Arts and Crafts" movement from Wright's beginnings.

The ideal for labour is self-fulfilment. Abb. 08

There is no administration - no bureaucracy - but the architect, who plans the city and settles its affairs. He arranges who may own how many acres of land and where roads start and lead to, thus preventing property speculation as well as congestion. Abb. 09

Broadacre is a continuous metropolitan region of low density. Areas designated to serve similar purposes are allocated functionally (parallel along traffic systems of more than regional importance like monorail and motorway):

trade, entertainment, industry, agriculture, housing etc.. Arrangements are selective - idealized - but not exclusive. Abb. 10

The city starts with the single family house. Due to Broadacre's economical logic it is being built by oneself (in a DIY network).

Using standardized elements and partly prefabricated building modules it is fairly extendable (in Wright's terms "organic"). But first of all it is affordable, although money has almost no relevance in Broadacre.

The Usonian House as a typology evolves. Abb. 11

Wright time and time again takes up the concept for simple, cheap "low-cost-housing". Such as American System-Built Houses 1911-17 (American System Ready-Cut), Quadruple Block Plan 1900, or Suntop Houses 1939-40.

Several alternative variations result from the Willey Houses, of which some actually get built. The propagated cost limit of 5000 dollars however, was never kept. [ ...]

Abb. 12

Mobility and information conveying systems are prerequisites for Broadacre.

In 1935 Wright esteems the importance of "communication machines" as follows:

"Everywhere the voice and sight of men cause distances to vanish - they permeate through walls. Wherever citizens walk (in fact while they're walking), information, housing and entertainment are provided. Whatever one needs or inquires, it's always made available easily." IX.) 3 Abb. 13

The notion of an aircraft in everyone's front yard is a convincing image. (Illustration 13) Total mobility is inevitable. Abb. 14

The road is a symbol of individual freedom. Cars aren't simply contemporary or modern, they represent democracy itself. The technology to cross and to communicate long distance facilitates:

air, light and freedom of movement. IX.) 4 Abb. 15

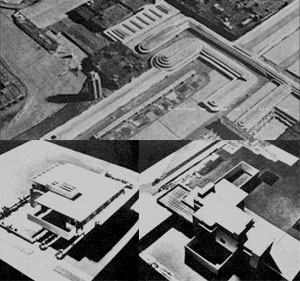

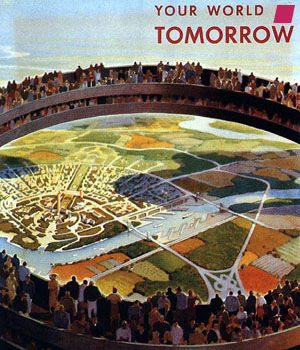

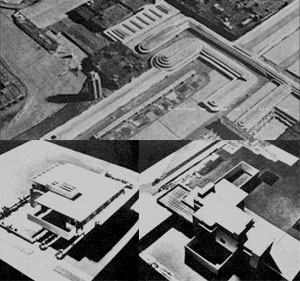

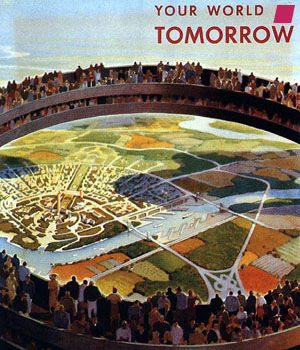

Expansions are in vogue, at least in America. 'Democracity' Abb. 15 is on display at the New York World's Fair V.) 8 in 1939.

Resolving the volume of traffic as well as coming to terms with prosperity shift focus. Horizontality and mobility are at the centre of attention in master plan simulations of the time. Abb. 16

By World War II at the latest, "The future isn't what it used to be." V.) 5

Instead of improving social order to achieve happiness for mankind, we apply technology to do so. Before, the new society guaranteed to handle progress reasonably - now advanced technology and science (considered an instrument to control these advancements) are trusted to solve the contradictions of current states. Abb. 17

Science Fiction replaces Utopia Abb. 18

Thus finally, projecting the future in architectural terms lacks all meaning. Urban visions are merely inhabited by monuments - crowded by samples, taken from architectural magazines. Abb. 19

By 1958 Broadacre remaines true to its socioeconomic concept, but generates different images. It sells via monuments, Frank Lloyd Wright's monuments.

The 'aerotor' becomes a trademark.

Wright's ensemble of monuments is brought to life in 1958 by drawings that have shaped the conclusive 'image' of Broadacre City

- representing the work of a lifetime: Abb. 20  Abb. 21 Abb. 21  - Butterfly Bridge, Spring Green, Wisconsin 1947

- Rogers Lacy Hotel, Dallas 1946-47

- Beth Sholom Synagoge, Pensilvania 1953-59

- Twin Suspension Bridges and Community Center, Pittsburgh 1947

- Huntington Hartford Play Resort, Hollywood 1947

- Self Service Garage, Pittsburgh 1947

(To the right of illustration 20; click image to enlarge)

- Gordon Strong Automobil Objective, Maryland 1925

- Marin County Civic Centre, San Rafael, California, 1957 - 70

(In the background of illustration 20 between c, b and e; as well as an inspiration in illustration 21) - [...]

Still, the concluding statement in Robert Fishman's 1977 analysis of Broadacre City constitutes the keenest critique possible.

"The Plan was democratic not because it had been debated in a legislature or approved in an election, but because it was representative of the nations deepest feelings." VII.) 6

References: - Arthur Drexler, THE DRAWINGS OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT - 1962 Bramhall House, New York

Abb.01 Abb.19 Abb.20 Abb.21 'Broadacre City' THE LIVING CITY - 1958, Frank Lloyd Wright - Neil Levine, THE ARCHITECTURE OF FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT - 1996 Princeton University Press

- Bruno Zevi, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT - 1994 (1979 Zanichelli, Bologna)

Abb.09 Abb.14 'Broadacre City' Model 1934 - 35, Frank Lloyd Wright - Brigitte Felderer (Editor), WUNSCHMASCHINE WELTERFINDUNG - 1996 Springer-Verlag, Vienna

Abb.18 'Clean Air Park' - 1959, Fred Freeman

www.fabiofeminofantascience.org

- Joseph J. Corn, Brian Horrigan, YESTERDAYS TOMORROWS; Past Visions of the American Future - 1996 The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (1984 Smithsonian Institution, New York )

5 (V) Arthur C. Clarke (co-author of '2001: A Space Odyssey' 1968)

Abb.13 'Crystal House' - 1934, George Fred Keck

for 'A Century of Progress Exposition' in Chicago 1933 - 34

Compare: 'House of Tomorrow' 1933 (also by Keck at the same fair) "View through hangar door showing airplane in place. […]"

Abb.15 (Page 45) 'Democracity' - 1939, New York World's Fair

"Created by industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss, Democracity [set in 2039] was essentially an updated version of ideas set forth at the turn of the century by British social thinker Ebenezer Howard [who] called for the decentralization of population and industry by the creation of garden cities. […] Democracity featured an urban core with tall, widely spaced buildings; separation of pedestrian and vehicular traffic; carefully delineated industrial and residential zones; and a generous greenbelt of farms and parks."

http://morrischia.com/

http://davidszondy.com/

Abb.16 'Personal Helicopter' - 1944, Alex S. Tremulis

Abb.17 'Moonport' - 1956, Jim Powers, Ford Motor Company

www.fabiofeminofantascience.org

8 (Compare pages 48-49) The New York World's Fair of 1939 themed 'Building The World of Tomorrow' also featured 'Highways and Horizons' [Futurama I], a vision for 1960 according to Norman Bel Geddes and General Motors as an alternative (?) draft:

http://xroads.virginia.edu/ (Full length Quicktime Movie)

http://www.archive.org/ (Various formats)

http://www.youtube.com/

http://gotfuturama.com/ Promotion Trailer (RAM) Right mouse click 'Copy Link Address' and paste into a new browser window as URL (won't play otherwise).

http://www.geocities.com/ (Description)

http://columbia.edu/ (Images)

http://fabiofeminofantascience.org/ (Images)

Also featured at the 1939 World's Fair was 'The City', a documentary by Willard van Dyke and Ralph Steiner. Part 1 and 2 available from http://video.google.de/

- Ken Burns, Lynn Novick, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT - 1997 The American Lives Film Project, Inc.

1, 2

Abb.03 Frank Lloyd Wright (at Iowa County fair, 1st of September 1933, filmed by Alden B. Dow)

Abb.05 Abb.06 Abb.07 Taliesin Fellowship (filmed by Alden B. Dow in 1933; part 1 and 2 available from www.youtube.com

roberto sanchez,RCDD

Facilius Per. Partes in cognitionem totius adducimur. Seneca -Es mas fácil entender por partes que entenderlo todo-

|

Boletín de Arquitectura

Boletín de Arquitectura RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright